Tagged: Summer Reading, Tramping, WTMC

- This topic has 1 reply, 1 voice, and was last updated 4 years, 1 month ago by Robert Jones.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

Tony GazleyMember

The inspiration for this article came from a talk by a fellow tramper. She detailed her foibles, fears and uncertainties in achieving her first summit on Mount Aspiring. I marveled at how she pushed her limits and wondered why she took on such a challenge. While I pondered her motivations, another tramper from the audience gushed to me about what a fantastic talk it was, how thrilling it was to hear someone so excited and so adventurous. Adventure. That’s the key.

As I reflected on the story of summiting Mount Aspiring that night, I considered the many times I have tested my limits and learned, all in the name of adventure. It brought up memories of how I learned to lead in rock climbing. I was tired of spending all my days in the gym, harassing friends to take me out to real rock and string up a top rope. Those friends must have been weary of my brash attitude because they didn’t offer to teach me how to lead. So I did what any adventure seeker would do—I got a second-hand book on rock climbing and talked less experienced (and therefore more naïve) friends in to going with me to the nearest rock climbing area. I figured my climbing was good enough to lead, my only challenge was that I had no idea what to do when I got to the top of the route and needed to set anchors and secure the rope to abseil. That day, I followed the book’s directions and successfully lead my first two sport climbs without any mishaps. Not much later, the more experienced friends realised there was no stopping me and began to teach me.

When I started to think about all my crazy odysseys, I wondered what stories were hiding amongst the experienced trampers and mountaineers of the club. So I started surveying fellow trampers. Not surprisingly people found it easier to remember the adventurous things others had done rather than their own mishaps. As a result, the following anecdotes are anonymous. Here are the nearly true confessions of WTMC adventure-seekers:

The very first stories people could recall were of things forgotten (or lost or misplaced). There were plenty of stories of forgetting gaiters, parkas, boots, insoles, dry clothes for the ferry ride home, etc. For some reason, many people had forgotten or lost their shorts and there were tales of walking in long johns in the heat of summer. There was the tramper that was certain her shorts had gone missing the morning after a long day of tramping. After copious searching by all members of the trip, she gave in, admitted they had walked off on their own and subsequently commandeered her partner’s shorts, only to find the missing shorts at the bottom of her pack after arriving home. Who hasn’t lost something on a trip only to find it sandwiched between the pack and pack liner at the end of a trip. But there’s really not much explanation for the punter who discovered someone else’s shorts in his own pack.

Imagine the jealousy of his follow punters when they all sat down to lunch and he whipped out a Big Mac and fries from McDonald’s. Some punters have shown quick-thinking in response to forgotten gear. There was the group that stopped in Otaki forks at an outlet store to purchase a replacement billy. Another group realised just after the ferry departed, that the billy had been forgotten; they managed to pinch an old billy left-behind at a hut when they stopped for lunch on the first day. Even more creative was the mountaineer who used his external metal frame pack to self-arrest when he slipped down a snow slope, having left his ice axe behind. Misplacing and forgetting gear is easy enough, but sometimes our ideas are a bit fraught from the start. Such as the intrepid tramper who decided not to bring a jacket for the trip to Kilimanjaro—because it’s hot in Africa. Or the newbie who went on the bushcraft course without a sleeping bag, hoping the summer weather would be warm enough. Apparently his friend shared the same cunning. He made a quick stop on the way to Platform 9 when realising he was supposed to bring lunch. Imagine the jealousy of his follow punters when they all sat down to lunch and he whipped out a Big Mac and fries from McDonald’s.

Just picture a glass jar full of olives still in their brine, a whole 10 kg pumpkin or an entire potted plant (soil and all) to ensure the coriander really was fresh. Food foibles were some of the most common stories of misadventure (at least we have our priorities right when we are facing the insurmountable). Imagine the extra weight from carrying ice zipped up in individual Ziploc bags all to keep salmon fresh. Or going for the extra energy in coconut milk with your muesli—and realising that you should have tasted it before you packed it for every morning of a ten-day trip. Of course you don’t need a taste test to know that custard without sugar won’t win any awards. More often than not, the mishaps involved misunderstanding directions for group food. There was the tramper who was asked to bring a vegetable to add to the communal meal. Instead he assumed he was bringing all of the vegetables for the entire 10-person trip and consequently brought a few potatoes, a head of broccoli, a head of cabbage and a few carrots. He hasn’t been the only one with a heavy pack due to food. Just picture a glass jar full of olives still in their brine, a whole 10 kg pumpkin or an entire potted plant (soil and all) to ensure the coriander really was fresh. Then again, having more food might be better than the poor new tramper who assumed all the meals were communal and had failed to bring anything for lunch, breakfast or snacks.

Imagine the extra weight from carrying ice zipped up in individual Ziploc bags all to keep salmon fresh. Even when all the right ingredients were brought along, packaging undermined the meals. There were the potatoes packed too close to the fuel bottles on a kayak trip, which despite washing, still tasted a bit strange from the leaked fuel. There was the carefully prepared food drop of a week’s worth of food packaged in paint cans welded shut and delivered to a pilot with exact coordinates for where to make the drop—only to find the cans, after a few hours of searching, a couple of kilometres from their intended destination, split open and strewn across a rocky outcrop. At least there had been an attempt at protecting the food, unlike the leg of ham which was left out overnight and managed to acquire blowflies. As the only other food on the trip was Whittaker’s chocolate bars and porridge, the crew had to pick off the maggots every night before slicing off the evening serving.

Sometimes, despite best attempts, our ingenuity just goes awry. When camping on a remote beach with a limited water supply, the team figured the best way to preserve water was to boil up the pasta in sea water. It made sense as one usually adds salt to pasta water—it didn’t make sense when they tried to eat it. At least they had intended on the salty experiment. A punter on a kayak trip offered to fill up the billy for a cuppa. After one experienced trip leader had drained his cup, someone else wondered why the tea tasted just a bit unusual. The billy-filler-upper answered ‘I just filled it up from the lake’, while pointing to the Marlborough Sounds.

The group can usually tackle the challenges of forgotten gear and food blunders by pooling resources and brainstorming inventive solutions. But sometimes in tramping, the mistakes we make aren’t so easy to resolve and we just have to survive the consequences. The search for sound sleep is a constant challenge, especially for the tramper who brought only a three quarter length Thermarest to sleep on frozen ground. At least her sleeping bag was dry. One tramper ended up feeling like a drowned rat when her sleeping bag became soaked with humidity accrued during the first night of the tramp because she slept inside her pack liner. She was attempting to stay dry despite being in the precarious position as the end person under a large club fly in the middle of a rain storm. At least that punter should be happy to have a sleeping bag. Imagine the disappointment of the tramper who discovered upon arrival at the hut, that his sleeping bag had been left behind on the track. He had unpacked on the way uphill to retrieve the first aid kit, after slightly stabbing himself with an ice axe, and managed not to repack his sleeping bag. Persistence, and in some cases, just being stubborn is often what carries us through the challenges we encounter. Consider the tramper who had to wade out to the middle of a tarn to retrieve a fly which was delivered there by gale force winds. It slipped from her hands on the fifth attempt at pitching it, which she was doing because she thought sleeping outside the hut would be quieter.

An oncoming tramper on his way out to finish the tramp that day, offered to give up his old boots (due for replacement anyways) in exchange for hut shoes. It’s not just sleeping bags and flies that become uncomfortable when wet. Surprisingly hut shoes fail to serve their purpose when, after a long fit day of tramping you meander down to the stream to fill up the billy too tired to perch on the rocks and instead stand in the stream forgetting you’re wearing said hut shoes. As we all know, having shoes is far more essential than keeping them dry. Surely the tramper, who took off his boots for the first river crossing at the start of the Wilkin-Young Circuit, neatly tying the laces together and swinging them over his shoulder, only to watch them wash downstream when he slipped in the river, can attest to that. Fortunately, that tramper was graced with the generosity that often travels with the adventure-seeker. An oncoming tramper on his way out to finish the tramp that day, offered to give up his old boots (due for replacement anyways) in exchange for hut shoes.

Yet, even when you have your boots, something as simple as your socks can let you down. There was the tramper who survived the summit of Mount Angelus in winter relying on cotton socks from the Warehouse. He was convinced the secret was simply to buy a new pair before every tramp. Apparently the expiration date on Warehouse socks is only about two days, because on the third day, when walking out past Lake Rotoiti, the tramper’s feet were in such excruciating pain he was forced to hobble with two sticks. As he fell behind the group, he stopped to rest. Smiling tourists approached him and he breathed a sigh of relief that they might offer to at least carry his pack…but instead they took his picture, giggled and wandered on.

Mount Angelus proved challenging in quite a different way for another tramper who found himself climbing late at night out of the tent on Sunset Saddle when nature called. Since he was too tired to strap on his crampons and his ice axe had been used to help stake the tent against the strong winds, he crept only a few paces away. His footing slipped, but he managed to steady himself in the snow just enough to avoid toppling down the valley. He was lucky he hadn’t ventured far from the tent—thankfully the tramper’s code (as I learned from the next story) requires one to take only five steps from the tent when stepping out to pee at night. That was fortunate for the tramper who had also taken the requisite five steps in the middle of night without his head torch, only to discover the following morning that the precipitance edge of Cascade Saddle was just six paces from his tent.

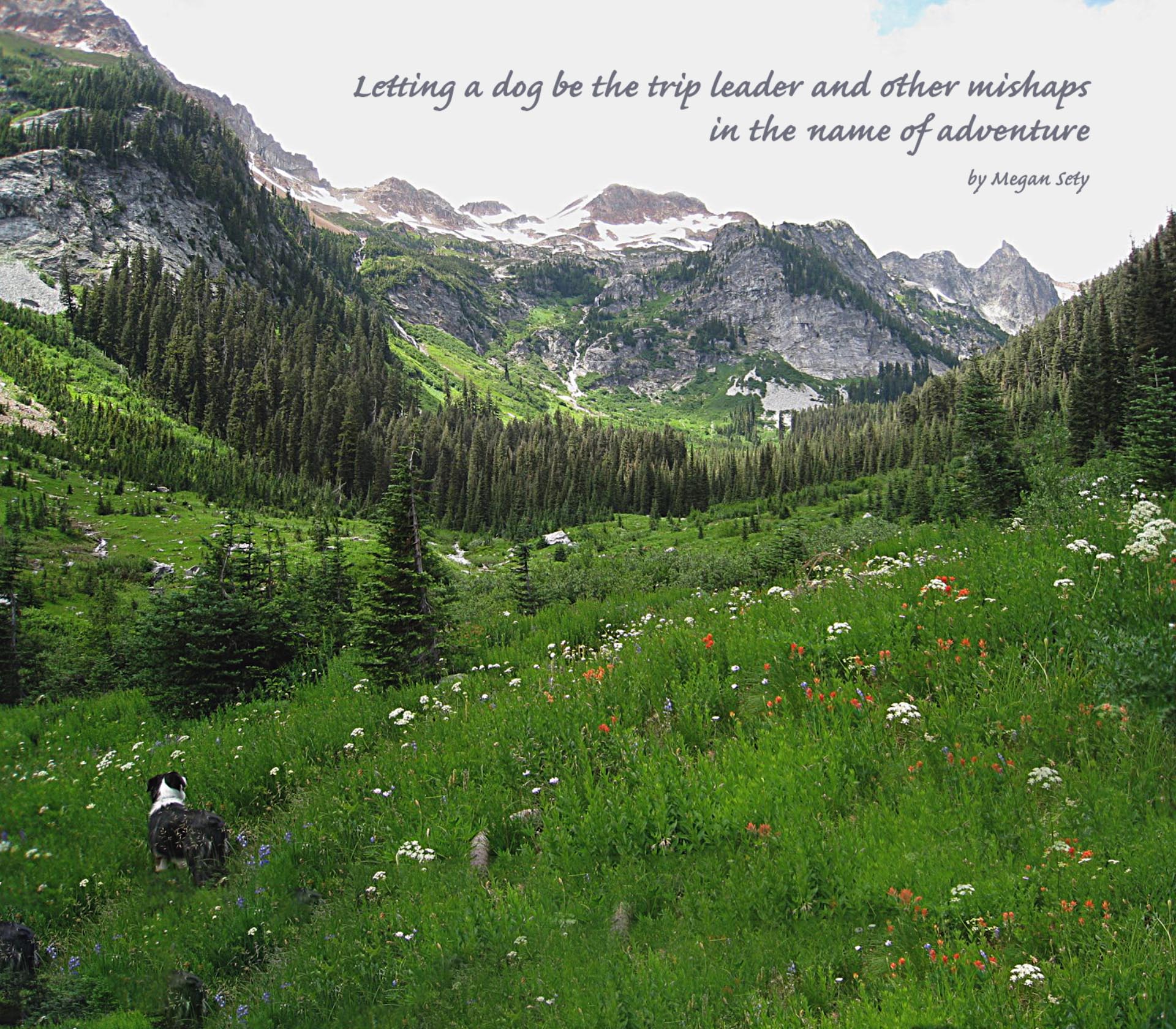

Beyond experience and planning, beyond persistence, creativity and collectivism, the real skills in tramping are responding when it all goes to custard with a belief that we will succeed when reality suggests otherwise. Take my own last story as a case in point. A friend and I had run into large snowdrifts on the second of a three-day tramping trip. Despite a lack of poles or orange triangles, we initially found it easy to pick up the track on the other side of the snowdrifts. But as the drifts grew in length, it became harder to find our way. Fortunately Trotter, my friend’s dog, had come along with us for the trip. He always ran ahead scouting the route and this time he proved useful, as sometimes he would run ahead on the snow more than a kilometre before finally picking up the track for us each time. After some time, when we finally caught up to Trotter, he seemed to be making circles. Indeed, the drifts had become snowfields and there was no longer a track to find. We realised we had been walking for more than an hour without looking at the map to confirm our location or progress – instead we had been relying on a dog to lead the way. I know I’m not the only tramper who has laughed when they found themselves in such a predicament, only possible because we made the decision to set out for an adventure in the first place and survived to tell the story.

From a story written by Megan for the 2013 WTMC annual journal.

-

Robert JonesGuest

VERY funny

-

-

AuthorPosts