What better way to spend the long Labour weekend of the 2011 Rugby World Cup Final than isolated in the second best mountain range for tramping in the world? I certainly couldn’t think of a better way: it was easy to wing my way back to New Zealand and head into the Ruahines! I stapled myself to a club trip being organised by Illona, with some personal goals being to bag more DoC asset numbers, and to keep my tramping gear sparkly clean for getting back into Australia.

What better way to spend the long Labour weekend of the 2011 Rugby World Cup Final than isolated in the second best mountain range for tramping in the world? I certainly couldn’t think of a better way: it was easy to wing my way back to New Zealand and head into the Ruahines! I stapled myself to a club trip being organised by Illona, with some personal goals being to bag more DoC asset numbers, and to keep my tramping gear sparkly clean for getting back into Australia.

Over three days we’d loop around through the high point of Piopio (1437m), Ruahine Corner Hut, and Ikawetea Forks Hut, and back to where we began. The route follows the circumference of some private Maori settlement land at the northern end of the range. It’s mostly conservation land, despite some being outside the official Ruahine Forest Park boundary. We saw no signs to indicate as such, but found later that we weren’t certain if the entire route remains on public land, although the Walking Access Mapping System (WAMS) suggests there’s a marked DoC route across the sliver of private land at the northern end. Best to check with DoC to be certain in future, though.

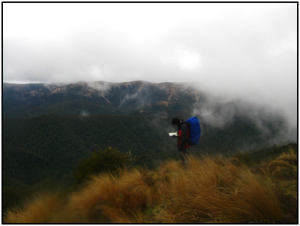

We arrived at Masters Shelter, roughly west of Hastings, around 11pm having obtained several litres of flavoured tap water from Carterton because the shelter has no drinkable water. It seems Masters Shelter has no DoC asset number … a demoralising beginning. Light drizzle settled, and when we left at 8am for the 800 metre climb up Golden Crown Ridge the morning provided a general greyness. Not too murky, though, to obscure the dampened scenes of the surrounding landscape with its reds and browns and greens of the dracophyllums and tussocks into which we were entering. I was relieved to discover that 10 months in the generally flat city of Melbourne hadn’t crippled me too much to reach the top. (Even searching quite hard in Melbourne, the only up-hill I could find on a daily basis was an inconvenient fire escape stairwell!)

It took 2 hours to reach the upstairs level of the Ruahines, from where it’s often possible to skittle in all directions with little undulation. I bagged my first asset number for the long weekend at the track junction at the top; DoC signs are a common place to find asset numbers. From this 1300 metre elevation we shifted from an up-hill grind into a coasty roll along the tops. Nobody else took much interest as I bagged more DoC numbers when we ignored a route left south towards Parks Peak, and our first main stop (for lunch) was Aranga Hut. It’s an old Forestry Service hut, now in private hands (as part of various settlement deals), though there’s nothing on the hut to indicate this. Sadly with the new arrangement it’s fallen into serious disrepair, with vandalism and holes in the wall, and the mattresses that remain are disgusting. We hid from the drizzle for lunch, but nobody wanted to put anything on the floor. I found more water from the tank, despite most of the gutter that feeds it being busted, but only after checking there were no dead possums, snakes or crocodiles on the roof.

Being resigned to finding no asset tags at Aranga as a non-DoC structure, I nearly missed the number on the back of the nearby sign that pointed towards Kylie Biv. The sign had a digit which recurred 3 times in a row. It was a 5!

Fun fact: Did you know that the chance of spotting a DoC asset number that includes three identical digits side-by-side is approximately 1/25? You could search for an entire weekend and not find such an asset number! The chance of finding three fives side-by-side is about 3/1,000. Three zeroes side-by-side is much more likely than any other digit, assuming DoC will never make use of that 6th significant figure.

We followed the generally flat plateaus in the muted shallow ridges of the northern Ruahines, passing nearly indistinguishable high points and saddles, eventually to the 1437m high point of our weekend (Piopio) to see a sprinkling of leatherwood. It occurred to visit Kylie Biv and escape likely overnight rain, or even press on to Ruahine Corner, but we decided to stick with the more predictable camping option after an assessment of how people were feeling. At the next significant tarn, we created a small campsite for ourselves on the tops at about 1420 metres.

At least, we tried to create a small campsite. Illona and Kevin found the pole of their borrowed club Huntech fly was snapped, and I discovered that the pole of my own borrowed club Huntech fly was missing the knob thingee that lets it fit through the eyelet on the fly, and that the fly itself was missing a couple of the plastic attachments for pegging it to the ground. Fortunately we were able to improvise for the rest despite the non-ideal conditions. (Please check and report these things before you return them to the gear room. Broken gear makes a happy tramper saaad! It could also become seriously bad on occasion.)

Two of the three flies had been set up with a low profile, which is what you get when people are too awesome to bring walking poles, and this made it difficult to slide in and out of a 30 cm gap without disrupting the pegs and getting horribly muddy… not consistent with my goal of remaining clean. The two happy couples chattered away, and I acted anti-socially in my own enclosed kingdom. After some awkward manoeuvring we had a yummy dinner that evening, thanks to Illona’s arrangement of a vegetarian quinoa and pomegranate molasses. I thought about sliding out and offering to do some dishes, but before I was able I heard neighbouring Illona volunteer Kevin for the task.

Speaking for myself, I learned much about the aerodynamics of Huntech flies that night, with this being the first time I’ve set one up in reasonable wind without some kind of shelter (like lots of trees). We’d set them up facing with the backs directly into the light southerly wind as is manufactory recommended so the air would flow over them, hoping everything would clear up overnight for a brilliantly still and clear Sunday. I woke about midnight to the angry melody of a fly rattling noisily in the light southerly as an aerofoil effect sucked the fly upwards, mildly disturbing because I wasn’t sure how well I’d pegged and tied down the corners against that sort of pulling. By 2am the sucking effect was gone, and instead the wind just pounded an already low profile and sopping wet fly straight down onto my bivy bag. Instead of a light southerly, it turned out that there was now a moderately stronger northerly, and therefore the flies were facing completely the wrong way. Some time afterwards I heard Richard a few metres away “heroically” re-hammering pegs. The memory is a blur but I think in concern for destroying my own fly’s fragile structure with a reckless act like crawling outside, I tried to help him out by making conversation instead. I don’t think he offered much chatter in return.

Night became another murky morning that remained consistent with the day before, albeit windier. I scraped together a cold breakfast, donned decent storm gear, packed everything except my groundsheet and fly, and sat crumpled inside the cramped arch of a cocoon that was slowly deteriorating as it was pressed heavily from above, waiting until Illona, Kevin, Amanda and Richard had done the same. Sliding out was a muddy activity, again not conducive to keeping my gear sparkling clean, but once outside it was clear that the wind wasn’t as bad as it’d felt. Amanda and Richard had had similar issues to myself overnight, and without bivy bags they now had a couple of damp sleeping bags. Fortunately there’d now be a whole day to figure out that problem.

We left just before 8am, continuing to a mushy plateau of tarns before turning more north-west-wards to find a couple of signs that confirmed our way towards Ruahine Corner; the sign half-buried in a leatherwood bush wasn’t in DoC’s database. The route took us through more dracophyllum and eventually a fern-covered landscape, and by 11am we climbed to the big plateau where one can find several more DoC asset numbers including the one with a well-loved hut attached.

Ruahine Corner Hut had a couple of hunters down from Auckland. They’d flown in a few days earlier but, as is often the way, had preferred to sit inside the hut with the cosy fire than actually spend any time outdoors. The hut is a cute standard forestry service box, though earlier this year some helpful DoC employees have dressed it in a deck and veranda to fit the latest fashion trends. Supposedly most people fly in, and there’s an airstrip outside, but judging by the time we made in a group it’d be very accessible by foot with a long day of reasonable fitness and not much stopping, certainly from Masters Shelter. We exchanged greetings, I photographed the hut’s number inside the door, we stopped for lunch, and they gave us some loose directions towards a warratah-marked route through the clouds and tussock to the 1234m trig across the plateau.

This is the furthest north I’ve been in the range. It feels different from the southern end which (whilst still allowing one to cruise around the tops all day) has sharper and narrower ridges. In contrast, some of the ridges we’d already encountered here are a good 500m wide on top. The maps don’t show many close contours around the plateau north of Ruahine Corner, but there’s still a landscape to circumvent.

We pushed through tussock, first to the furthest 1234m trig (there are two 1234m spot-heights), then along the tops of the bluffs to 1206m, under which we sat snacking for a short time as some rare sunshine desperately tried to break through the clouds. The bluffs shown on the maps aren’t all big cliffs so much as a series of overhanging rocks, which provide several places where it’s possible to scamper down with no technical skills. Illona had good information about a trapping line from spot-height 1206 down to Ikawetea Forks Hut, and not far inside the bush-line we located a horizontal line of orange markers which looks to be for catching people no matter where they slip in as long as it’s roughly below that point. It leads to the top of a descending trapping line that’s been marked to death with pink tape nearly all the way down the spur towards Ikawetea Forks Hut. We followed it to a little gully just west of the hut, and dropped to Ikawetea Stream on a steep route. This led to our first significant river encounter of the long weekend, with the hut somewhere on the far side. Not knowing exactly where to look, Kevin and I checked up-stream slightly, and discovered a messy steep route that could be uncomfortably scaled with the help of overhanging tree roots. From there we found Ikawetea Forks Hut, and also the much more sensible route we could have used had we followed the river in the other direction.

Nobody was home at Ikawetea Forks (DoC Asset 43453), but a couple of hunters had left things. We had no idea if they’d be back that evening or not, but simply arriving was a relief because Amanda wasn’t feeling well (and hadn’t been for the whole trip), and Illona had copped a rock on the back of her leg during the last steep drop towards the river. It was when all our gear was spread outside, trying to dry with limited success under the cool shallow sun, that I was down at the river and looked up from frustratingly scraping the mud from my un-sparkly gaiters and saw the two hunters stumbling awkwardly through thigh-deep water. I waved and smiled, trying not to give an impression that they’d have a full hut tonight. They’d been away for three days, were due to fly out the next day, and (so they said) had successfully crawled back with 50+ kg packs full of meat. As a 7-bunk hut, there was enough mattress-space inside even with the five of us. The two chaps were locals from Hawkes Bay, and were happily chatty enough for us to learn more about local routes. They tried to pass themselves off as vegetarians when Illona’s curry-laksa meal came out. I snuck down to the river a few times that evening. It’s a nice place. My turn for dishes.

We woke on Monday morning and evidently the world hadn’t realised that this Monday was a holiday, because the sun was finally visibly rising. Keen on not getting home too late, we were away soon after 7am, waved goodbye to the hunting chaps, hopped across the river, and began the second 800m climb of the long weekend, though it’s really only steep for about the first 500 metres and then it shallows out before the final upward jump. 2.5 hours into the day, having emerged from the bush-line underneath the mighty Tauwharepokoru, a famous 1403 metre peak of the Ruahines, we stopped in the morning sunshine for a few minutes, relaxed in the make-shift tussock-laden couches, and gazed north-west toward the lesser snow-sodden hillocks of Tongariro National Park.

From here it’d be a straightforward walk around the circumference of the tops. The route is mostly well marked with a combination of waratahs, foot-trails and 4WD tracks, though it could be exposed on a windy day. We were momentarily lost when trying to follow waratahs early-on, I think in the sludgy muddy area around Ikawetea (which we later discovered is private land, albeit seemingly with a DoC route marked through it according to the WAMS). Only one climb along this section is notable, which is about 100m upwards towards spot-height 1314 shortly before returning to the top of Golden Crown Ridge, and we arrived at that junction about 6.5 hours into the day, leaving nothing but a 90 minute jaunt back to where we’d begun, and bringing Labour Weekend to an end. Another 16 distinct asset numbers independently documented. Not a bad jaunt for the second best mountain range for tramping, and I couldn’t think of a better way to have spent the time.

I completely forgot to wash the mud off my boots as I passed the farm-tainted stream at the end of the day, and the muddy boots left me with a tougher scrubbing job later that night. For better or worse, it seems you have to push Australian biosecurity agents from Victoria beyond the point of irritation to get them to look at your gear, and I lost the argument.