Aimee visited the Sub-Antarctic Islands and Antarctica in January 2020 and writes about the part of her journey that fascinated her the most – the wildlife.

The hurricane force winds, towering waves and bitter cold of the Southern Ocean might lead one to think that the Sub-Antarctic Islands and Antarctica must be inhospitable and lifeless places. That, devoid of life, there is little to see, to entertain, or to connect with. But this is a narrowly human perspective. Travelling south with Heritage Expeditions, I found a natural auditorium filled with characters and stories that rivalled the very best in human theatrics. Set against a backdrop of unspoiled landscapes and impossible living conditions, I have never been so captivated in my life.

The drama started long before we reached the icy continent. Bobbing around in zodiacs off the coast of the Snares (Tini Heke), a minuscule island chain 200 km south of New Zealand and so named for its ability to wreck the unwary sailor, we were treated to a cruel opening scene. A Snares-crested Penguin carcass rose and fell on jubilant seas. Around him, a tight and angry circle of Giant Petrel snipped and tore at the little lifeless body with bulbous keratin bills. On the shore a mass of suited penguins stretching the length of exposed terrain stood hypnotized by the scene. It was as if they were frozen to the spot by the terrible end of their brother.

Mother nature can be as capricious as any lead actor, and our next stop at Enderby Island, at the north-eastern tip of the Auckland Islands (Maungahuka or Motu Maha), proved her such. We found a long, white sandy beach that looked somewhat out of place for a sub-Antarctic island. Peppered along the beach were hundreds and hundreds of New Zealand sea lions. Dads, mums and pups. Dad stood defiantly with nose in the air, occasionally expelling a haughty breath or bark, and eyeing up the visitors with some suspicion. Mum looked exhausted from fighting off the unwanted attention of a male. She sought refuge with her female companions in bobs on the beach, or tried to claim a solitary spot further inland amongst the grass and trees. And the pups. Little fat sausages piled up high on the beach or bravely wriggling out from underneath to find mum. One such bub in front of me struggled to keep his balance on stout little flippers and tail, and over he tumbled, down onto the beach, flattening a scavenging skua.

Even further south we found the capital city of the sub-Antarctic’s, Macquarie Island. Property is pricy here, with landing spots hard to come by. The zodiacs were swarmed by King penguins, bumping the sides of the boat and launching themselves inside, as they scrambled for a piece of rubber real estate. On the beach both King and Royal penguins conducted the important business of waddling backwards and forwards, to a choir of farts, burps and bubbles escaping from car-sized lumps that turn out to be elephant seals. A mouth gaping wide to give you a silent scream, or the flick of a flipper to throw up some sand, will let you know that this is not a rock to sit on. Oh the fast-paced life of the big city!

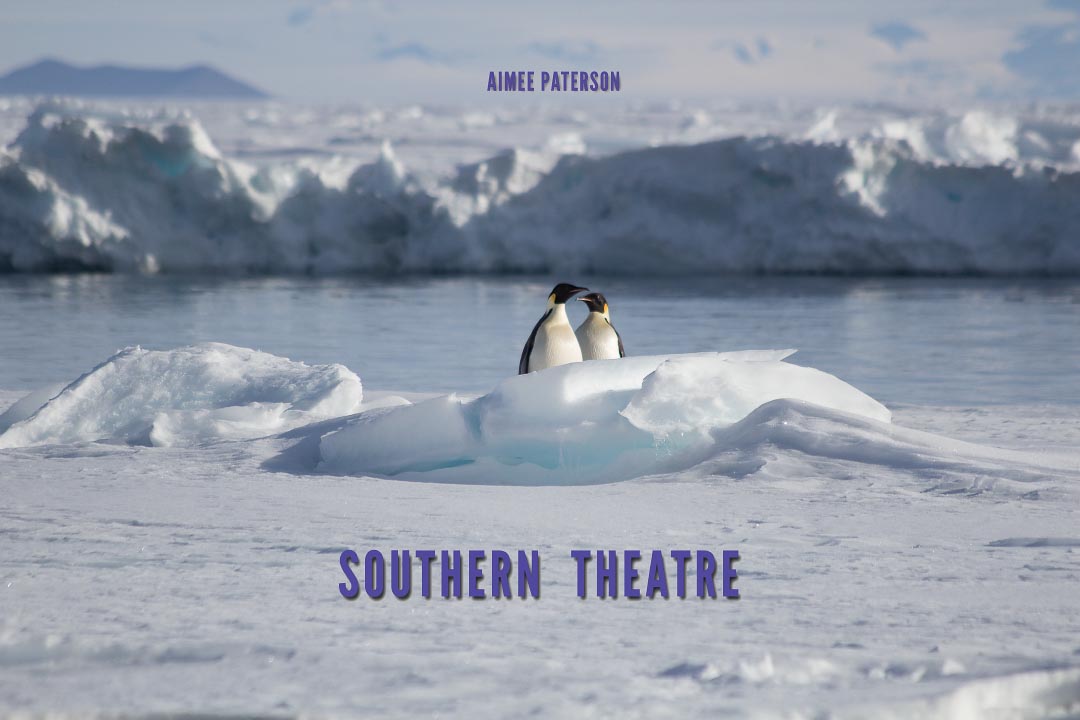

Anticipation built as we ventured further south. First one iceberg, then another, and we had crossed the Antarctic Circle. It became eerily quiet, with only the sound of the bow carving its way through ice bergs. But even here the drama of the natural world continued, at a micro level. Hanging over the sides of the boat we could see flipped broken ice revealing a yellow tinge – the result of algae colonizing the bottom of the berg, and tiny krill holding on for dear life. Every now and then, a leopard seal would be spotted lounging on a piece of ice in the distance, his stitched grin evoking an unsettling comparison with the modern Joker, or a lonesome Emperor Penguin would waddle into view, providing us an opportunity for a quint-essential Antarctic photo.

It was a glorious evening when we first sighted Cape Adare, our first landing site on continental Antarctica. The sun dipped behind the Admiralty Mountains, scooted sideways, and was forced to rise again, having not been able to beat its way underneath the horizon. At midnight we were sitting in the zodiacs, speeding our way to shore, in awe of the landscape in front of us. It was here, and later at Possession Island and Franklin Island, that we were treated to the inner workings of Adele colony life.

Over 1 million little amigos spread out before us, occupying all of the flat land and slowly creeping up the cliff faces, nesting at the most outrageous of angles. After the silence of ice-covered seas, their chatter was clamorous.

“Don’t touch that pebble, it’s mine!”

“I’m hungry, feed me!”

“Stop pecking me!”

“Who are these big tall aliens?”

The adults purposefully waddled about, either going out to sea to fish or coming back in with a full belly to feed their chicks. Some were still building (or repairing) their nests, covertly stealing pebbles from another. A handful of unlucky suitors were trying to get a head start on next year’s nest. The chicks were by contrast, largely still, either standing upright with head snuggled down into their downy breast, or lying down due to weakness. Every now and then, a harassed adult would come careering through the crowd, hounded by a couple of surprisingly mobile, if chubby, chicks demanding a feed. The adult would be tackled to the ground by his plucky pursuers. Little beaks would poke at him until he gathered enough will or strength to fight off the fluff balls and make another run for it. The rough and tumble of raising a little one will be familiar to parents of all species.

The South Polar Skua had become the lead villain in this drama. He was always circling overhead, looking for his next prey, or perched aloof on the side of the boat, surveying us with disdain. He was even known to dive-bomb you if you ventured to close to his nest. On the steep slopes above Franklin Island’s beach, I caught a glimpse of why. The clean and cotton-like downy fluff of a skua chick was easily observable against a backdrop of rock and dust. On little legs the fluff ball wobbled its way after the parent, who was keeping a close eye on the chick’s progress. I had a sudden change in feeling towards the Skua. Young life in such a hostile environment is indeed something to guard closely.

Turning our attention to the frigid Southern Ocean waters, they were undoubtedly the domain of the Orca, or the “type C” Orca to be exact. I puzzled over why they were called “type C”. I had heard of “type A” and “type B” personality theory, but no mention of a “type C”? Was this a combination of the two, or perhaps some third rebellious personality type that did not fit either mould? Of course we were given a suitable scientific explanation by our excellent guides, but I persisted with the idea that type C orca were the non-conformist, melancholy and wayward characters of the Antarctic world, as if they were permanently stuck in their teenage years. Again my random musings were borne out by the evidence, as they only ever appeared when I was not on the bridge or bow, or when my camera had run out of battery or space. So fickle.

The plot climax was reached in the form of the Weddell Seal. I did not expect to be so enchanted with an animal that I was only peripherally aware of, as the life-sustaining blubber factory for early Antarctic explorers. Weddell seals have beautiful big dark eyes, long eyelashes and fur like a Persian blue cat. Their flippers are short and close to their face, and I was enthralled with the way the held these limbs up to their chest in an exaggerated and feminine manner. Although I did not witness it myself, the seals of Possession Island sang to each other, an ethereal and alien kind of noise. I spent some time watching them loll about on the ice, unfussed by my presence and observing my occasional movements out of sleepy eyes. Surely the appearance of Madam Weddell Seal was the high point of this drama?

Not quite. The Southern Ocean had one more little surprise for me. Campbell Island (Motu Ihupuku) has its own store of charm, largely comprising of incredible stories of species survival. As someone who works for the Department of Conservation, the New Zealand government agency charged with managing the Island, I was especially keen to see the fruits of the Department’s collective labour. In 1975 a small population of Campbell Island Teal were found on a rocky Islet, Dent Island, off the coast of Campbell Island, having disappeared from the mainland due to predation by rats. Eleven were taken back to New Zealand to breed. By 2004, the Department had removed all the rats and began repopulating Campbell Island with Teal. Fast forward to 2020, and they are now populous enough that it took less than 5 minutes for our guide to find one on the shores of Campbell Island, and I came bill to nose with decades of dedicated conservation work.

Coming home to the human-built world, I wondered just how many ecosystems we have flattened, species we have obliterated, and stories we have missed out on in pursuit of shaping the natural world for our comfort. The reputation of the Sub-Antarctic Islands and Antarctica as inhospitable and lifeless has so far protected it from the reach of the manipulative human hand, and preserved this slice of Southern Theatre for a few incredibly lucky individuals to enjoy. Long may it remain that way.

Wow, Aimee, what a fantastic trip you had! I enjoyed your descriptive narrative with photos, and it now gives me more incentive to pursue my intention to travel to Antarctica one day. As a former Tongue and Meat (1966-1969 – some of the older generation members may remember me; I left to travel overseas in January 1970) I like to read about fellow travelers’ adventures, especially when “off the beaten track.” I now reside in Arizona. Hope to see more postings by you in the future.