Tararua Range –

what are some of its faults?

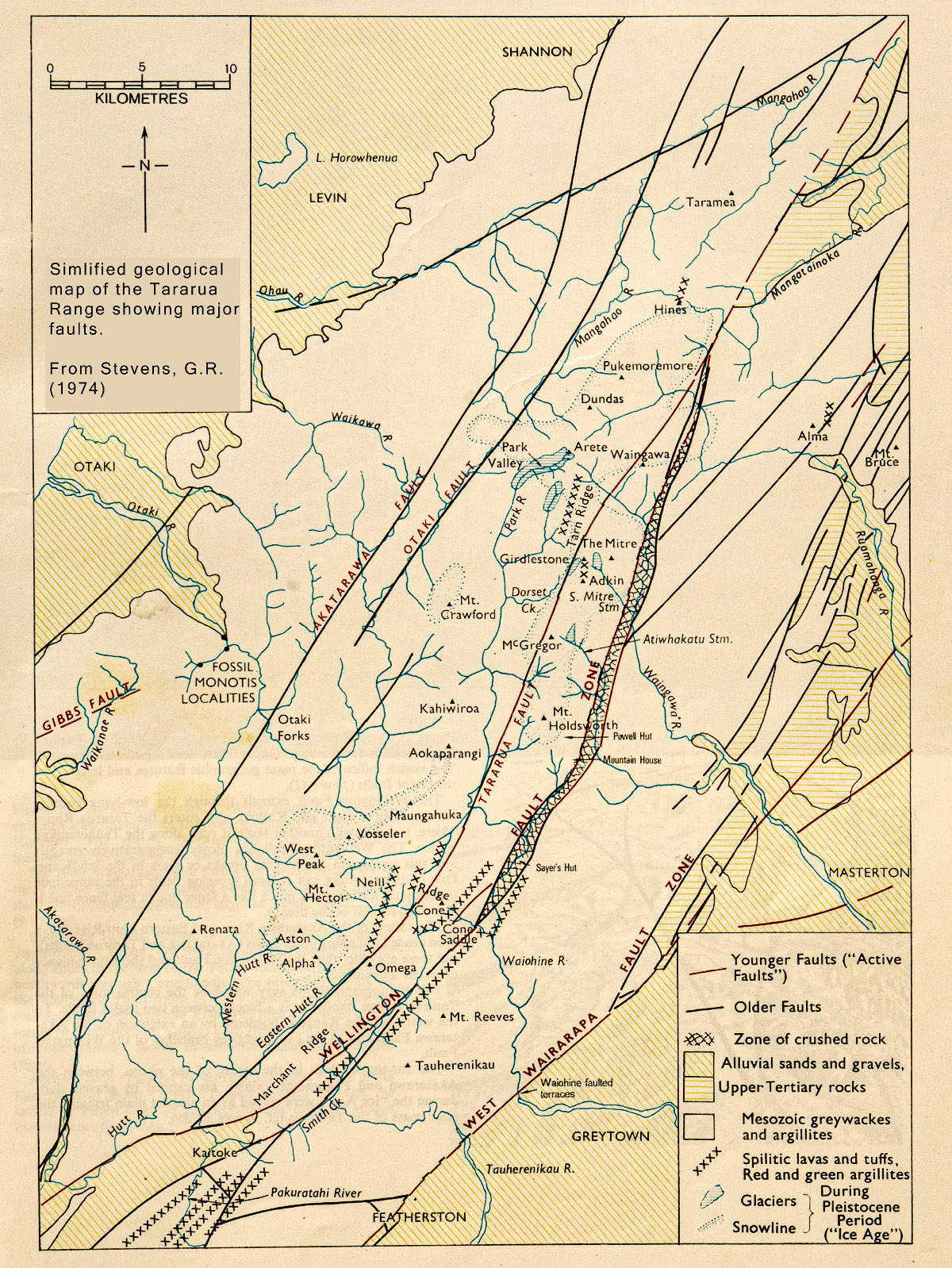

The Tararua has many earthquake faults, and the Wellington Fault and the Wairarapa Fault have left many obvious geomorphological features visible to the hiker.

🌧

One of the faults of the Tararua Range is that it rains a lot and there are only about 80 sunny days per year. But there are actually quite a lot of another sort of faults of the Tararua too—and these are its earthquake faults.

One of the most active is the Wellington Fault that comes ashore on Wellington’s south coast, carries on up Long Gully and through Karori, under Parliament Buildings and the InterIslander ferry terminal, along the western side of the Hutt Valley, past Kaitoke—where it takes a 2 km side-step to the east—up the Tauherenikau Valley, over Cone Saddle, and then right on through Totara Flats—although the fault scarp is not visible through the flats themselves but is about 500 m to the west among the trees. The fault then continues up Totara Creek, across Pig Flat, along the Atiwhakatu and Waingawa Valleys, across Cow Saddle before finally leaving the Tararuas at Putara and becoming the Mohaka Fault after it crosses the Manawatu River.

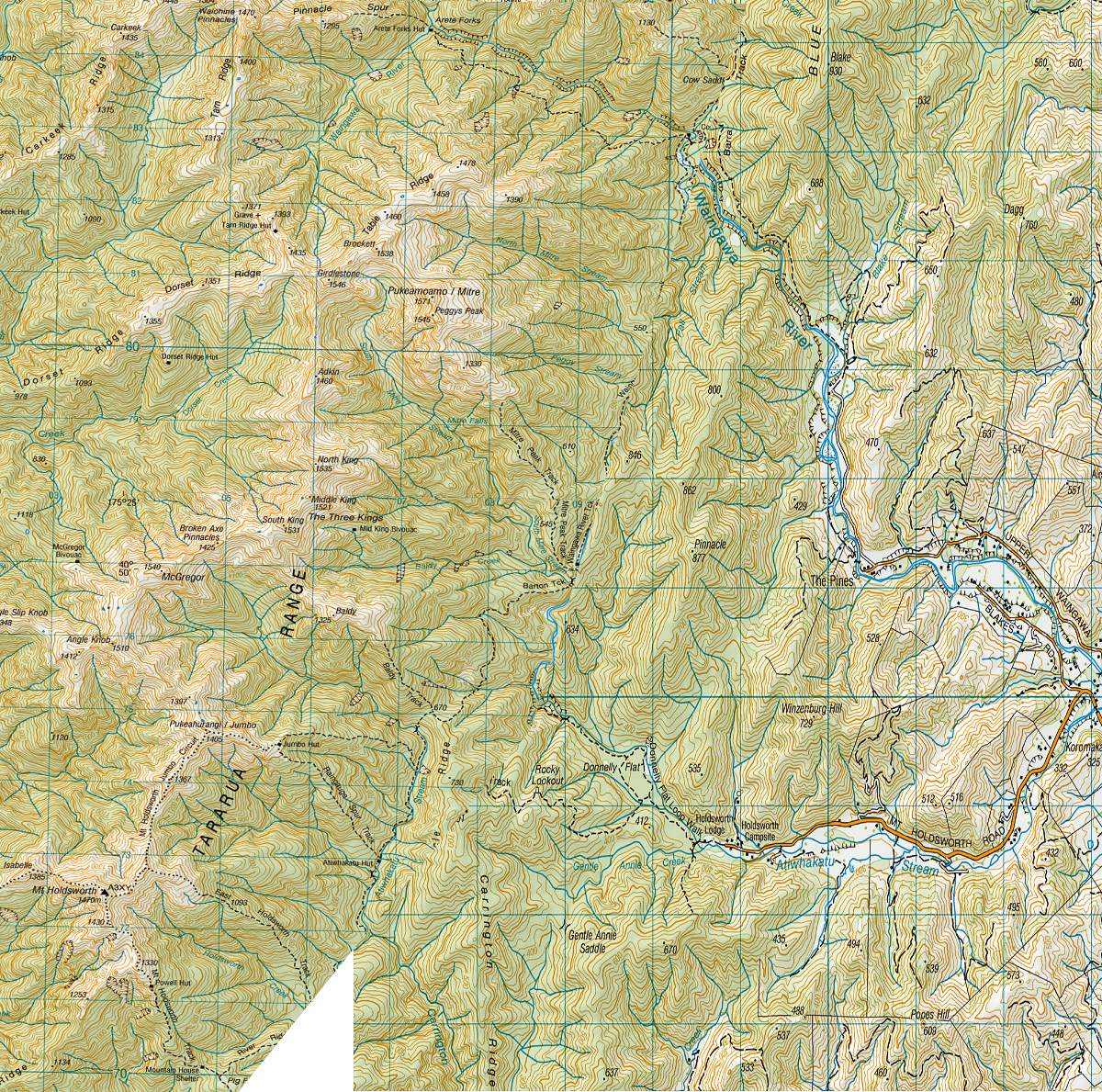

Perhaps you have noticed that most of the main rivers on the Wairarapa side of the Tararua start by running towards the east, then suddenly turn south for about 7 km, before abruptly turning eastwards again as before. Well, if you get a Tararua map and cut along the line of the Wellington Fault and then move the western piece a map distance of about 7 km south you will find many of the rivers join up again and happily run eastwards without the southward kink.

The Ruamahanga, Waingawa, Waiohine, and the Tauherenikau are ‘straightened out’ while a lot of the smaller streams join up in interesting ways. For example, South Mitre Stream becomes the headwaters of the Atiwhakatu, while the Atiwhakatu is the headwaters of Carrington Creek.

The reason for the odd kink is because during the life of the Wellington Fault since the Tararua Range drainage patterns were established, the western side has moved about 7 km north relative to the eastern side over a period of between 0.8 and 1.3 million years—and the rivers have been forced to flow that distance south along the line of the faults before being able to once again flow eastwards out towards the coast.

Geological evidence points to the Wellington Fault being divided into three separately active segments—from Wellington to Kaitoke, Kaitoke to Putara, and Putara northwards. Each of these segments have ruptured either separately, or possibly sometimes together, many times in the past. One rupture on the Tararua segment approximately 500 years ago caused significant landsliding in the Tararuas and the resulting debris buried an existing forest at Totara Flats. Boreholes made recently at the flats showed the trunks of large forest trees still in their growth position but under 3 m of gravel. The existing Totara Flats may well suffer the same fate sometime.

The Wellington Fault shows itself with other well-known features too. When climbing from the Mountain House Shelter to Powell Hut you climb up the scarp of the fault. Similarly, when climbing from Mitre Flats Hut (which is sited directly on the Wellington Fault) to Peggy’s Peak.

Other significant faults in the Tararuas are: the Tararua Fault which is a branch of the Wellington Fault and runs along the Eastern Hutt River, across Hell’s Gate, between Holdsworth and Isabell, and northwards to re-join the Wellington Fault at Mangatainoka; the Otaki Fault that follows the upper Otaki River; and the Akatarawa Fault that passes northward through Otaki Forks and on to Shannon.

Additionally, defining the eastern side of the Tararuas is the West Wairarapa Fault that last ruptured in 1855 with an estimated 8.2 to 8.3 magnitude earthquake causing uplift of about 2.7 m at the fault and 1 m in Wellington with considerable damage to the buildings of the early settlement.

Geological evidence along the Wellington Fault shows that, based on elapsed time since the last event compared with the average recurrence interval, the Wellington to Kaitoke segment of the fault is not yet overdue to rupture (but is in the ‘window’) which is perhaps good news for Wellington City, but that the Putara northwards section has not ruptured for at least 1,100 years and that the prior interval was only about one third to one half of the present elapsed time so it is likely that it is this segment of the Wellington Fault that will rupture first in the future—with a possible magnitude 7.4-7.8 earthquake.

Oh well, just add it to the list of faults of the Tararuas …!

That is remarkably interesting so thanks for sharing Tony. I guess many of us will be paying more attention to signs of the scarp of the Wellington Faultline next time we head up to Powell Hut or Mitre Peak.

You are right, Tararua Range does indeed have several faults (and yes in more ways than just seismic). But if it were not for the faults, we would not have a Tararua Range given there’s evidence the mountains began as sediments under the sea millions of years ago.

I like what you did with the Topo map. You have saved us having to visualise. I had fun working out some new routes. According to your modified Topo map, our easy out-and-back trail run along to Atiwhakatu Hut would now be through to Mitre Flats hut. The carpark for the Jumbo-Holdsworth circuit (if going anti-clockwise) might remain at Holdsworth Lodge, but although we would still head up Gentle Annie, we could bypass Rain Gauge Spur and take the alternate track up to Jumbo instead. The road end for Mountain House and Powell Hut would perhaps change to an access road off Mangatarere Road.

Another interesting geological wonder of this part of the North Island/Te Ika-a-Māui is how the Manawatu River starts out on the East of the Ruahine Range and should flow across to the East Coast but instead takes a turn West and heads to the Tasman Sea.

Heather.

Hello Heather. It is fun imagining trips in the Tararuas 1 million years ago and you came up with some interesting options. Now you should try planning some routes for trampers 1 million years in the future – leave the Holdsworth carpark and walk up the Atiwhakatu to Totara Flats Hut maybe.

And I like your perceptive comments on the Manawatu River. Not many people are aware just what an ‘oddball’ river it is – collecting run-off from the eastern sides of the main North Island axial ranges and then flowing to the coast on the west. It was the only river able to cut down through the mountains ranges faster than they were rising – others gave up and flowed to the east.

But it doesn’t end there. Look at the course of the Manawatu River between the gorge and the sea – it doesn’t simply flow directly westwards to the coast but instead it wanders southwards almost to Levin before northwards again to the sea. And the reason for this is it has had to flow around ‘buckles’ in the surface where tectonic domes (more like ridges actually) have formed and which are still actively rising today (very cleverly it has sneaked between the Himitangi Dome and the Levin Dome or else it would have had to go even further south).

And for a while during the last ice-age (50,000 years ago) because of lowered sea-levels it had to flow an additional 45 km to reach the sea. It’s had a varied life …

Tony.

Ha-ha, walking up the Atiwhakatu to get to Totara Flats. If that happens, then Putara road end will be too far south for Herepai so the S-K may need to start from around Kakariki making it the K-K challenge.

As for the Manawatu River, it is like a ribbon on the end of a kite. Long with so many bends. I have always marveled at how far south we cross it when heading up SH1 when we know how far NE and on the other side of a range the headwaters are. Yes, the Manawatu is unique. Imagine the stories she holds.

Heather.

The Mangahao River (one of the main southern tributaries of the Manawatu) is even odder. It effectively arises on the western side of the Tararuas, or at least it arises within the Tararuas on the western side of the main axial range, which runs up Dundas Ridge, though Hines, and up through Burn Hut (and continues through Mairehau and Ngauwhakaraua north of the Mangahao Gorge). But instead of flowing out to the plains to the west of the Tararuas, which is what you might expect (perhaps down the course of the Tokomaru river), the Mangahao then turns east and cut right through this main axial range through the Mangahao Gorge and out to the plains to the east. It then joins the Manawatu River, which then cuts right back through the main axial range through the Manawatu Gorge and out to the sea.

So effectively the Mangahao starts on the west, flow through the ranges to the east, then flows back through the ranges to the west – and all because the rivers were there before the mountains started rising.

Harry.